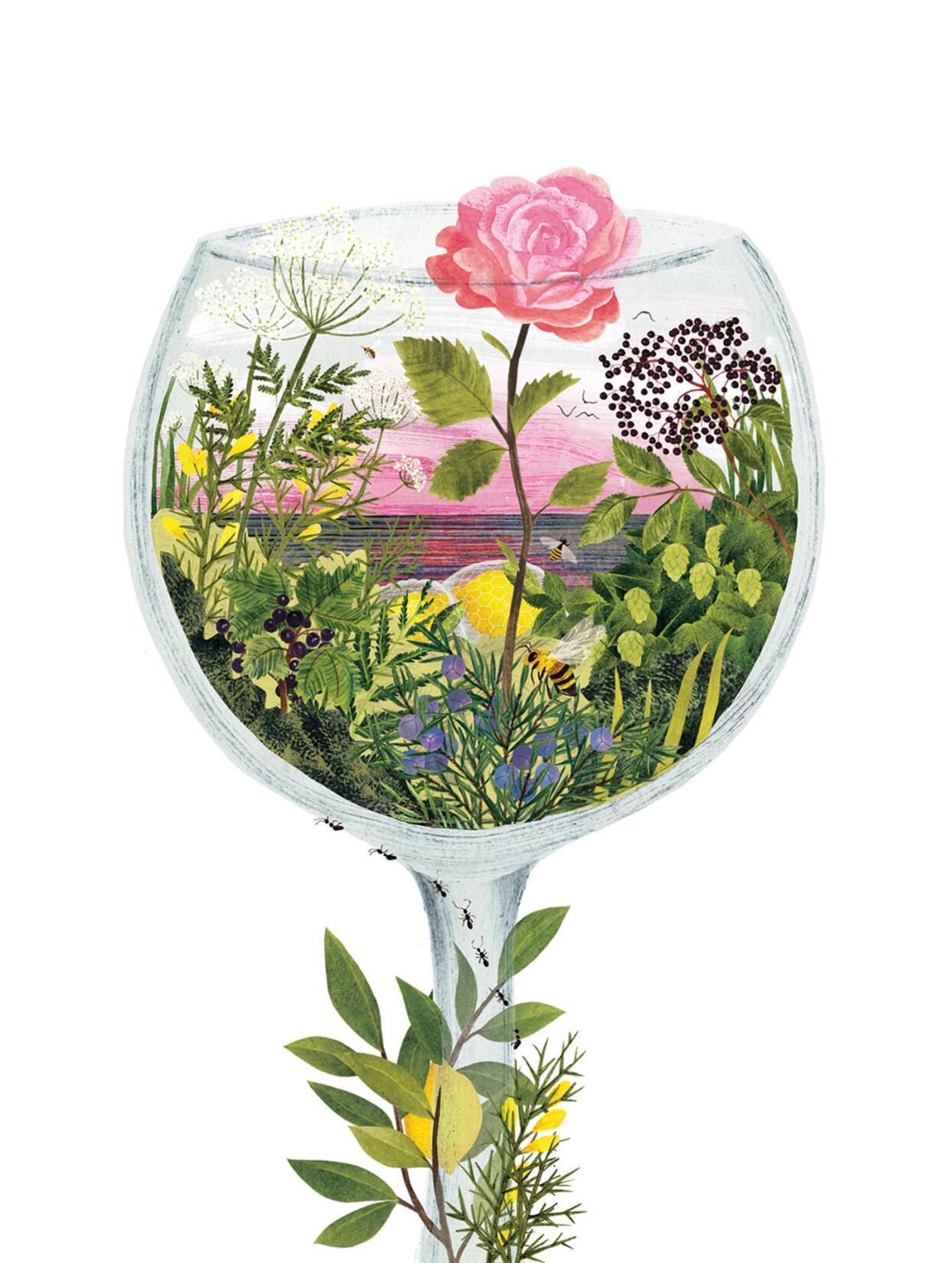

One of the great legacies of these drinks is vermouth, an aperitif which started life in 18th century Italy, and which is now experiencing a wonderful renaissance in distilleries around the world. In its simplest form, vermouth is just a fortified, sweetened wine flavoured with bitterest wormwood. But most vermouths are flavoured with dozens of botanicals. At the Sacred Distillery in north London, they make an amber vermouth from English wine and botanicals including thyme, savory, cherry and plum stones. The South African vermouth Caperitif, meanwhile, is laced with more than 35 ingredients harvested from around the Western Cape: sour figs from the dunes, citrusy naartjies, cape gooseberries, kei apples. There are vermouths flavoured with lemon verbena, lavender, citrus peels, cinnamon, raspberries, vanilla, nutmeg, liquorice, rosemary and even myrrh.

Some of these recipes read more like perfumes than drinks. And there was a time when perfumes and libations were almost interchangeable (distillation was, after all, invented not to make strong liquor, but to capture essences to make scent). The earliest eau de colognes, with their uplifting notes of citrus, exotic flowers and herbs, were elixirs designed to be worn or imbibed. In the 19th century, there was also a fashion for adding ambergris – a rarity more often used by perfumers – to alcoholic punch.